|

|

I.

Introduction I.

Introduction

II.

Mies van der Rohe and the Creation

of a New Architecture on the IIT campus

III.

About Rem Koolhaas

IV.

Rem Koolhaas's IIT McCormick

Tribune Campus Center

V. An Interview

with Rem

Koolhaas

In

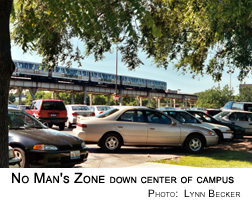

his essay “Miestakes,”Koolhaas

describes the current IIT campus as marooned...swimming in space.”

It had been “scraped” clean of its urban  density,

he says, and a long period of decay had resulted in the “disappearance of the city around it.” Now “it is no longer

a void in an urban condition, but it is a void in a void.” And within the campus

was still another void, where the Green Line and a long strip of surface parking lots cut the dorms to the east off from the classrooms to the west. density,

he says, and a long period of decay had resulted in the “disappearance of the city around it.” Now “it is no longer

a void in an urban condition, but it is a void in a void.” And within the campus

was still another void, where the Green Line and a long strip of surface parking lots cut the dorms to the east off from the classrooms to the west.

Koolhaas - whose blue-chip roster of participants in the Campus Center

project includes the Chicago firms Studio/Gang/Architects

and Holabird & Root,

as well as international powerhouse Ove

Arup - rejected the competition's requirement that the different functions

of the Campus Center be stacked in a multistory building to muffle the

noise from the “L.” He opted instead to "make a very flat

building" in which the different elements-sports bar, bookstore,

post office, cafe-would continually rub up against one another, creating

new hybrid activities and a “simulation” of the dynamics of

the urban condition. The “culture of congestion” in a single

building.

For two days in 1997 Koolhaas used a team of students to track movement across the campus through the project site. They came up with a web of heavily traveled paths, which Koolhaas turned into walkways through the building that divide it into a “series of islands,” each with its own function and visual character.

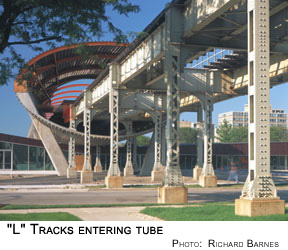

He also had to address the problem of the “L” and what he called

the "acoustic disaster zone" it created down the center of campus.

The roar of the trains hit 110 decibels there-the pain threshold is 85. The project manager, Ed Newman, jokes that the standard IIT greeting was “to

put both hands over your ears and yell 'Hi' as loudly as you can.”

In their proposal Jahn and his associates had come up with the relatively inexpensive idea of laminating rubber blocks and strips along the flanges of the tracks, which their research showed would significantly decrease

the noise (something the city ought to consider trying out in the Loop).

Koolhaas's solution was more symbolic and expensive. He rejected the idea

of using the building as a shield, preferring to muffle the noise of the

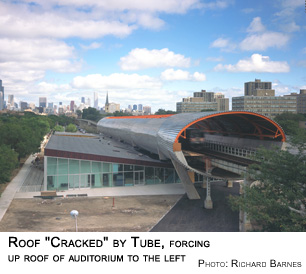

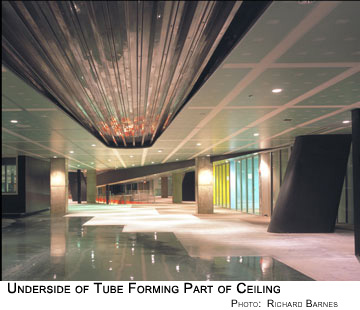

“L” by surrounding the tracks with a spectacular 530-foot elliptical

tube, faced in stainless steel, whose underbelly forms part of the Campus

Center's roof. The tube is isolated on a series of columns that reduce vibration by descending

62 feet to the bedrock. He told the competition judges, “We think

it can be done for something between a million and a half and two million,”

but the tube ultimately cost more than $13.6 million, paid largely out

of George Ryan's Illinois FIRST goody bag.

is isolated on a series of columns that reduce vibration by descending

62 feet to the bedrock. He told the competition judges, “We think

it can be done for something between a million and a half and two million,”

but the tube ultimately cost more than $13.6 million, paid largely out

of George Ryan's Illinois FIRST goody bag.

The Tube was completed last year, and inside the Campus Center the sound

of the “L” is barely audible, though north of the structure

the trains still drown out conversation. The Tube's slanting concrete

supports and flaming orange top serve as a symbol of the renewed campus-the

new IIT student Internet portal even calls itself “The Tube.”

As for the Campus Center itself, for Koolhaas

more is more, and a whole lot more is better still.

Much of the center's drama stems from the way he's packed an astounding variety of levels, ceiling heights, materials, and finishes into the single story. “People say the interior is going to feel like being inside

a pinball machine,” says architecture dean Donna Robertson. “But

18-year-olds really have a different way of engaging with the world than

you or I. They're used to responding to multiple layers of information,

and their response level is incredibly quick. They get this right away,

and they love it.”

Jeanne Gang, who

studied and worked with Koolhaas and whose firm is one of the project's contractors, says, “There's an interest in creating

the conditions that will bring chaotic activity-and finding that as a

joyous thing instead of trying to control and separate functions.”

“I think it's destined for architectural glory,” says undergrad

Robert Guico, who took an early tour. “I really noticed the change in elevation. When you walk in, there's bigger rooms that you actually look down into.”

The design of the roof derives from the metaphor of a violin, crushed

along its center by the Tube above it. It's a continuous concrete slab

that wraps over the  edges

of the building and slopes up to cover the higher ceilings of the ballroom

and auditoriums along State Street. “It's sprayed with a black synthetic

membrane that's overlaid with a burgundy of the same material,” says

Studio/Gang's

Mark Schendel, “and it results in a very beautiful wood-grain pattern.”

Yet it's already controversial, perhaps because the visible seams in the

membrane compromise the idea of wrapping the edge and the burgundy overlay edges

of the building and slopes up to cover the higher ceilings of the ballroom

and auditoriums along State Street. “It's sprayed with a black synthetic

membrane that's overlaid with a burgundy of the same material,” says

Studio/Gang's

Mark Schendel, “and it results in a very beautiful wood-grain pattern.”

Yet it's already controversial, perhaps because the visible seams in the

membrane compromise the idea of wrapping the edge and the burgundy overlay looks less like stained wood and more like the color of beer nuts.

looks less like stained wood and more like the color of beer nuts.

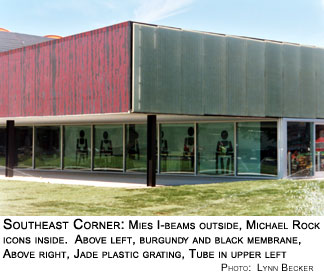

The membrane is just one example of the explosive range of materials and

finishes at the center. Orange, the keynote color in the building's palette,

is a unifying theme. It's crucial to Koolhaas's concept of a wall of “Miesian

interference” that wraps around the facade and faces off against

Crown Hall. The black Mies used to paint his steel reflects the qualities

of his buildings -elegant,  strong,

and protecting, but also mysterious and forbidding. Orange is seen almost

as its opposite - happy, warm, generous, and invigorating, but also overbearing

and superficial. strong,

and protecting, but also mysterious and forbidding. Orange is seen almost

as its opposite - happy, warm, generous, and invigorating, but also overbearing

and superficial.

Orange “straw glass” dominates the center's northwest corner.

“I'm waiting to see whether the pickets come out along State Street,”

Robertson had said before the wall went up, only half joking. The glass

covers the Welcome Center and the entrance, split into two vertical rows of panes, in places the topmost

extending above the roofline as a translucent parapet. During the day the space

directly inside the windows takes on a marmalade glow. Koolhaas says that

though the scale of the center is “very modest” compared to

Crown Hall, the orange of his building “somehow brings out the color in the Mies building also - not

only by contrast, but also by raising the issue of color. You suddenly see

much more color in Mies.”

Each panel of orange glass consists of two outer panes, between which

is a honeycomb wire mesh that during the day bends the outside light into

nimbuses of suns  and

at night sends arcs of headlights coursing across the windows. The same

type of “tube core” glass, minus the orange tint, makes up the

entrance walls of interior offices. and

at night sends arcs of headlights coursing across the windows. The same

type of “tube core” glass, minus the orange tint, makes up the

entrance walls of interior offices.

South of the entrance the orange folds inside the building, moving onto

the high back wall of the auditoriums as a sunny zigzag made of a new DesignTex wall covering that's like a 3-D baseball card, creating the illusion of movement as you walk past it.

Green complements the orange. On the eastern facade the concrete walls

of the upper mechanical-services area are covered with a translucent pale

jade, egg-crate-like plastic that conceals the ventilation system's massive

louvers yet allows air to flow freely. The sign over the east entrance

is made of orange-faced metal cylinders, mounted in holes of the grating,

that form the letters of the building's name.

egg-crate-like plastic that conceals the ventilation system's massive

louvers yet allows air to flow freely. The sign over the east entrance

is made of orange-faced metal cylinders, mounted in holes of the grating,

that form the letters of the building's name.

Inside,

the concrete columns that support the “L” tracks are left bare.

The large, slanting columns that support the tube are painted black, looking

a little like the smokestacks of a sleek ocean liner. Throughout, the

beautiful, slender versions of Mies's classic I-beam that support the

structure are left exposed, as is the single black beam that stretches

high up inside the windows along almost the entire length of the ballroom/auditorium

section on State.

Green epoxy covers the flooring of the sunken, Center Court sports bar,

as well as the adjacent grand staircase, which incorporates a wheelchair

ramp which rises at so gentle a slope that no railings are required. The

most beautiful surface, in an area earmarked for pool and Ping-Pong tables,

is an opalescent green the texture of the sea, polished to such a high

gloss that it seems almost liquid.

The floor is crisscrossed by aluminum walkways that mark the heavily traveled

pathways Koolhaas's team laid out in 1997. The standard carpet is a silver

and black stripe, and in many offices, a white wall faces off another

wall in  blackboard

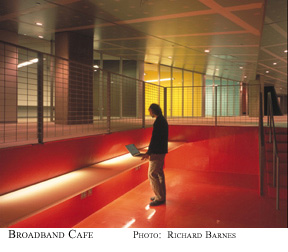

finish, ready for chalking. The trench that forms the broadband cafe,

ramped to fit below the Tube, is surfaced in a deep maroon epoxy. blackboard

finish, ready for chalking. The trench that forms the broadband cafe,

ramped to fit below the Tube, is surfaced in a deep maroon epoxy.

Another

unifying theme is Koolhaas's use of Panelite,

a sheet of fiberglass or polyester resin with a honeycomb core that comes

in a variety of textures, colors, and transparencies and weighs about

half as much as plate glass. Koolhaas used shimmering gold and silver

"Sponge"

pattern Panelite for his New York Prada store. For the Campus Center he

chose translucent Panelite for the countertops in the cafe, for the tables

in the study carrels that overlook the Mies courtyard, and, most strikingly,

for the walls of the freestanding, amoeba-shaped washroom that sits just

inside the entrance, opaque enough, alas, to preclude any anatomical shadow

puppets.

In the middle of everything is a large glass “hanging garden”

that's open to the sky but completely sealed off from the rest of the

center. “The building,” says Schendel, “is amazing in the

sense that you can stand in it and look through to the outside, back to

the inside, back to the outside, back to the inside several times-like

a shish kebab of space.”

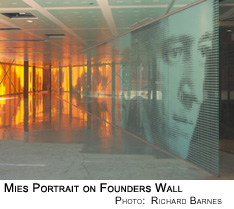

Koolhaas's engagement with Mies

is apparent the moment you walk in the door, because Mies is in

the door-an 18-foot-high portrait of him is sandwiched between the panes

of glass, so that you walk into the building through his head.

through his head.

This kind of iconography plays a big part in Koolhaas's design, reflecting

Robert Venturi's conviction that in our electronic information age “architecture

should reject abstract form” of the Miesian variety and restore iconography

as the “essential architectural element.” As he explains, “Egyptian

hieroglyphics on pylons are like billboards; early Byzantine or Christian basilicas...have interiors teaming with signage-we call it high art....It was only in the twentieth century that they got rid of iconographic communication.”

Koolhaas asked New York graphic designer Michael

Rock to create imagery that, according to Donna Robertson, “comes

out of the Gothic tradition in  campus

architecture, where the gargoyles would carry jokes...comments on the

nature of academic life-the professor professing and students snoozing.

It reminds you that we are moving to being more image based than text

based.” Rock created a series of two-and-a-half-inch-round icons

- a “swirlies” icon to indicate washrooms didn't make the final

cut - that are used in multiple ways. On a white interior wall set just

inside the glass of the building's south facade, they're supersized to

form a single row that stretches floor to ceiling. Much smaller versions

are embedded along the surface of the stainless steel bulletin board,

scaled to where the round magnetic icons used to secure postings can rest

atop the shoulders of each iconic figure as a whimsical second head whose

only facial feature is the inscription "IIT." campus

architecture, where the gargoyles would carry jokes...comments on the

nature of academic life-the professor professing and students snoozing.

It reminds you that we are moving to being more image based than text

based.” Rock created a series of two-and-a-half-inch-round icons

- a “swirlies” icon to indicate washrooms didn't make the final

cut - that are used in multiple ways. On a white interior wall set just

inside the glass of the building's south facade, they're supersized to

form a single row that stretches floor to ceiling. Much smaller versions

are embedded along the surface of the stainless steel bulletin board,

scaled to where the round magnetic icons used to secure postings can rest

atop the shoulders of each iconic figure as a whimsical second head whose

only facial feature is the inscription "IIT."

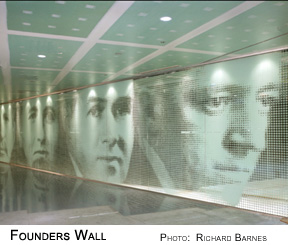

Most of the graphic images in the Campus Center are also made up of the

icons - they're like pixels in a sort of dot matrix pointillism. The Mies

in the entrance door is made up of them, and the massive “Founders

Wall” that dominates the building's welcome center consists of hundreds

upon hundreds of them. Step back, and the icons coalesce into seven nine-and-a-half-foot

portraits, including Mies again, Heald, Armour, Pritzker, and Galvin,

each “like a Chuck Close painting,” in the words of Mark Schendel.

Koolhaas sees the iconography as a response to globalization. “When

IIT opened you could probably assume that everyone would feel very welcome

in a highly

abstract space such as Crown Hall,” he says. “I think that if

the current generation enters a building like that they feel a weird absence

of information. Given the fact that the student body is now literally from

at least four or five continents, it felt very important to try to develop

a language of fundamental information that is effective in these circumstances.” highly

abstract space such as Crown Hall,” he says. “I think that if

the current generation enters a building like that they feel a weird absence

of information. Given the fact that the student body is now literally from

at least four or five continents, it felt very important to try to develop

a language of fundamental information that is effective in these circumstances.”

Just outside the Center Court sports bar is a garden courtyard, the site

of a heated controversy that broke out in

March 2000, before construction began. When Koolhaas's design for the

building was first made public, preservationists were outraged at the

way it dealt with the neighboring Commons Building, the original student

center. Completed in 1953, it was the only major structure in the central zone along State between the campus and the dorms.

Depending on whose story you believe, its design either came directly

from the pencil of the master, or from associate Gene Summers, after Mies

threw up his hands on the project when the school failed to come through

with funding for  Mies's

more ambitious Student Union building. Whoever the designer was, the Commons

Building was another Miesian masterpiece -an exposed-frame, glass-walled

pavilion with an open interior that won an American Institute of Architects

award. Mies's

more ambitious Student Union building. Whoever the designer was, the Commons

Building was another Miesian masterpiece -an exposed-frame, glass-walled

pavilion with an open interior that won an American Institute of Architects

award.

By the time Koolhaas got to the building it had suffered decades of abuse.

The exterior walls had been punched through to add vents and pipes, and

its open interior was cluttered with makeshift partitions. His commitment

to restoring it got lost in the uproar over his decision to have his own

much larger building suck the Commons inside it like Jonah into the whale.

Two of its exterior walls would become walls within the Campus Center,

and the other two would become linear extensions the far larger building's

far longer walls.

John Vinci saw this as a direct attack on Mies's “simplicity and

purity,” declaring, “The only reason to do this is to clash

with Mies.” He wrote a letter to the Chicago Tribune charging Koolhaas

with “wanton defacement.” Architect Stanley

Tigerman backed Vinci, calling the new structure “a slap in the

face, a very ordinary building that does great damage to the Commons.”

Vinci proposed that Koolhaas move his building south, leaving the Commons clear on all four sides, and that he convert the Commons to a visitors' center and faculty club. Koolhaas bristled at the idea. “To make

the Commons into a Mies visitors' center," he told the Tribune, "would

be to embalm a structure that was intended by Mies to be used.”

“John Vinci's protest actually had a lot of effect,” says Donna

Robertson.“It galvanized the attention of the IHPA

[Illinois Historic Preservation Agency], which, because we accepted the

Tube money, had the right of review of anything we built, even if it wasn't

the Tube.”

The school brought in Gunny Harboe, an architect who specializes in restoration, to consult on new ways to handle the two buildings. Preservationists

won a temporary victory in May, when the IHPA staff asked that at least

12 feet separate the two buildings, but by July 2000 the staff had reversed

their decision. Robertson and IHPA associate director Bill Wheeler contended

a “valid compromise” was reached, but Vinci isn't buying, “I

don't think I made any progress. I lost.”

The Commons Building is being repaired and its original open interior

restored. A roof for the Campus Center loading dock that cantilevered

over the Commons like a grasping claw was cut back. Robertson says that “superclear,

superwhite glass” was put in the eastern facade of Koolhaas's center

where it absorbs one side of the Commons to visually separate the two

buildings. The corner where the two meet is surrounded by the “Mies

courtyard,” the garden off the Center Court sports bar. Here the

foundation of the Commons has been dug out and clad in black painted steel.

like a grasping claw was cut back. Robertson says that “superclear,

superwhite glass” was put in the eastern facade of Koolhaas's center

where it absorbs one side of the Commons to visually separate the two

buildings. The corner where the two meet is surrounded by the “Mies

courtyard,” the garden off the Center Court sports bar. Here the

foundation of the Commons has been dug out and clad in black painted steel.

Mark Schendel says the Commons Building used to be “an orphan ...stranded

in a parking lot.” Now the courtyard offers a “magnificent view

of the Commons. I think you will see it in a completely new way.”

Nevertheless, exposing its foundation reduces the Commons to something

of an archaeological artifact.

Construction has been marked by a series

of “value-engineering” compromises intended to keep burgeoning

costs under control. That's not unusual for an innovative building, just

painful. Things wind up costing up more than anticipated; complications

ensue, economies are mandated. Part of the game of architecture is figuring

out how to make a great omelet even as they keep grabbing back back eggs.

“OMA built its practice on constraints,” says Schendel, and

Koolhaas has worked to keep his basic design intact even as he's been

forced to switch to less expensive materials.

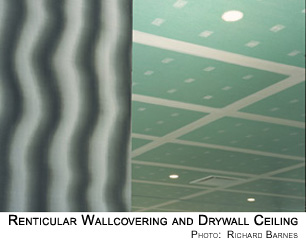

Koolhaas had originally planned to use wood for the building's ceilings,

but that was a budget buster. Wood is costly, and it's flammable, so a second,  fireproof

ceiling would have had to be installed above it. In many places Koolhaas

turned to a solution he'd used before-the unpainted green drywall would

become the ceiling. The white plaster “mud” used to cover the

screw holes joints and seams between the boards - usually applied quickly

and without any concern about aesthetics, since it's just going to be

painted over - is here applied almost with an artist's care, resulting

in a ceiling that's a continuous expanse of large green rectangles framed

in white, each rectangle daubed with twin rows of small white squares.

“It's important to have these vast expanses of exposed Sheetrock,"

says Koolhaas, "because this is a kind of return of Miesian puritanism

about steel, but in a more abject material.” fireproof

ceiling would have had to be installed above it. In many places Koolhaas

turned to a solution he'd used before-the unpainted green drywall would

become the ceiling. The white plaster “mud” used to cover the

screw holes joints and seams between the boards - usually applied quickly

and without any concern about aesthetics, since it's just going to be

painted over - is here applied almost with an artist's care, resulting

in a ceiling that's a continuous expanse of large green rectangles framed

in white, each rectangle daubed with twin rows of small white squares.

“It's important to have these vast expanses of exposed Sheetrock,"

says Koolhaas, "because this is a kind of return of Miesian puritanism

about steel, but in a more abject material.”

Elsewhere rare zebrawood became fake zebrawood, then a zebrawood-like

wall covering. Travertine became epoxy flooring inside and grass outside. Koolhaas has visited the site about twice a year. On one trip he was so unhappy that work was temporarily stopped. But when he returned at the beginning of July he was said to be excited by the progress.

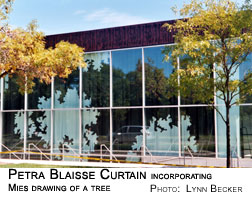

Work on the building is going right down to the wire. Just last week longtime

Koolhaas

collaborator and companion, Dutch interior and landscape designer Petra

Blaisse, could be seen in the auditorium supervising the hanging of

her 30-foot-high draperies, incorporating a Mies drawing of a tree, black

on white on the inside, white on black on the reverse. As dedication day

looms ever closer, questions about whether everything will be finished

in time are met with an almost mantra-like response: “It has

to be finished.” Koolhaas

collaborator and companion, Dutch interior and landscape designer Petra

Blaisse, could be seen in the auditorium supervising the hanging of

her 30-foot-high draperies, incorporating a Mies drawing of a tree, black

on white on the inside, white on black on the reverse. As dedication day

looms ever closer, questions about whether everything will be finished

in time are met with an almost mantra-like response: “It has

to be finished.”

Unlike Crown Hall, where you can imagine yourself, like Mies, sitting

alone atop that stack of plywood, and still having a wonderful experience

of the space, Koolhaas's Campus Center feels incomplete without the bustle

of the people it's designed to serve. It's as much a dynamic as it is

an object, and people will have to fill it before we'll know whether their

rubbing together will produce the sparks Koolhaas intended. What can't

be denied, however, is that the marriage of a group of users overwhelmingly

young, bright and receptive with a sympathetic client, determined to get

noticed, has both inspired Koolhaas and given him the opportunity to create

a building that's a dazzling showplace for his ideas.

At the moment Koolhaas is working on one other big U.S. project, the new Seattle public library, scheduled to open next year, and he's just won

a commission to build an 800-seat theater in Dallas. But like many architects,

he's hit a dry streak, and OMA's response has sometimes turned bitter.

Earlier this year his partner Ole Scheeren told the London Independent

that OMA had made a conscious decision not to join the competition for

rebuilding Ground Zero in New York. He explained that competing would

have meant choosing to “associate with . . . [a] nation that is at

the end of its greatness and propelling war plans into the world.”

In his essay, “Delirious

No More,” in the June issue of Wired, Koolhaas labeled Daniel

Libeskind's plan for Ground Zero “a massive representation of hurt

that projects only the overbearing self-pity of the powerful” and

“captures the stumped fundamentalism of the superpower. Call it closure.”

China seems to be the new focus of Koolhaas's enthusiasm. “Two billion people won't be wrong,” he wrote in Great Leap Forward. Scheeren

told the Independent, “It's the choice to associate yourself with

a regime that is on the brink of opening up and propelling itself into

a positive-thinking world.”

Koolhaas has been picked to design a new $600

million headquarters for CCTV, China's state television monopoly. At 700 feet, it will be the tallest

building in Beijing. China, with its booming economy and centralized control,

can still allow an architect to dream on a grand scale.

Of course the China that has allowed the remarkable economic growth of

the Pearl River Delta is the same China that privatized an effective public-health

system and left one billion peasants without access to adequate care,

the same China where this summer 350,000 people in Hong Kong protested

provisions of the proposed Article 23 so repressive they'd make John Ashcroft

salivate. Yet China is letting Koolhaas build, and for that he seems willing

to look the other way.

Asked if he thinks it's still possible to do good work in America, Koolhaas

says, “We're working in the United States, and IIT is one example, but

also we're doing the library in Seattle . . . it is really astonishing.

An architect isn't going to decide where he works. We had a phenomenally

strong project

for LACMA [the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; in a project valued

at $400 million] that went into the garbage dump and a phenomenally strong

project for the Whitney [Museum, for an estimated $200 million] that went

into the garbage dump. We wanted desperately to participate in a project

for the United Nations, but we were not invited.”

He decries the “fragility of cultural institutions in a country where

culture is financed by [private] gifts rather than by [state] subsidies,”

as it is in much of the rest of the world. But he insists he's here to

stay. "We have an office in New York that is open for business."

When

architects describe how they create their buildings, they

talk about logic and objectivity, but the more subjective element of personality

plays a stronger role than many would care to admit. How architects see

the world and how they respond to the values of their time can mark their

buildings as distinctively as fingerprints.

Mies would study a client's needs intensely and create reams of preliminary drawings, yet no matter what problem a project posed, the answer always wound up being a variation of the classic Miesian glass box. Koolhaas

also prides himself on doing intense research for each project, yet the results

always bear a highly individualistic stamp that can't be mistaken for

the work of any other architect.

For a bad architect, indulging personality is like giving a child a box

of matches and telling them to go out and play, but for the great ones,

personality is not a weakness, but a strength. It is their personality

that crystallizes the spirit of the time in their work, and drives them

to imagine themselves as creators of alternative new worlds that transcend

the annihilating failures of their era.

“Architecture

is an historical process,” says Mies. “It belongs to the epoch.” As one epoch fades into the next, values evolve. Mies, a

child of his time, believed above all in truth and in order, and he didn't see

order as an oppressive force. “The real order,” he said, “is

what Saint Augustine

said about the disposition of equal and unequal things according to their nature.” In his work this meant eliminating the things he didn't

think fit: curving walls, triangular facades, rounded roofs, oval rooms, diagonal corridors, bright colors, but the result was buildings of astonishing

clarity and grace, and a transparency offering an almost existential emptiness.

In our own time, when order is shunned as control and truth is often declared suspect, Koolhaas has other priorities. “I believe in uncertainty,”

he says in S,M,L,XL, and his Campus Center embraces the very architectural

elements Mies rejected. Yet he's also acutely aware of the downside of

our era's values. His 2001 essay Junkspace creates a harrowing

portrait of unchecked market forces expanding the world's capacity to

pump out ever larger quantities of just about everything, including architecture,

even as that architecture becomes relentlessly more generic. Koolhaas

responds with buildings that are as far from generic as you're likely

to get, all but bursting with ideas and intimations of better worlds.

Mies is about reduction and subtraction, Koolhaas about addition and multiplication. A Mies building is like a Bach cantata, perfect and crystalline.

A Koolhaas building is like a Mahler symphony, an attempt to capture the

complexity of the world in a single work.

It's important to remember that the “simpler” time in which

Mies built the IIT campus was a time when the world was engulfed in unspeakable violence. Mies tried to make an architecture that was both an answer and an alternative.

And that's the point where he and Koolhaas connect, though the link is

sometimes obscured by Koolhaas the writer's despairing depictions of our

time. Koolhaas the architect still allows for hope. “Behind every

project we do there is a kind of vast critical apparatus of doing better,” he says. “We're

not trying to emulate the current mess. We are just as interested in the

sublime.”

••••••

Intro

| Mies | Koolhaas

|

Intro

| Mies | Koolhaas

|  | Campus Center | Koolhaas

Interview

| Campus Center | Koolhaas

Interview

lynnbecker@lynnbecker.com

© Copyright

2003-2004 Lynn Becker All

rights reserved.

|