|

|

The United States is no longer a young country; Chicago is no longer a young city. Have we grown too accustomed, too dependent - of the things we've grown most used to? Have we been dulled into a maturity dominated by predictable, dehumanizing routine? "We think of all the buildings that try to be well mannered, that don't strive, that don't attempt to create a new future," says Joe Valerio, one of the architects whose work is included in "Chicago  Architecture: Ten Visions," a new exhibit that's on display at the Art Institute through April 3rd. "We look around and see all these buildings that are just incredibly dull and boring, and I think the show is interesting in the sense that it challenges you. Each room is in a way an act of civil disobedience." Architecture: Ten Visions," a new exhibit that's on display at the Art Institute through April 3rd. "We look around and see all these buildings that are just incredibly dull and boring, and I think the show is interesting in the sense that it challenges you. Each room is in a way an act of civil disobedience."

Of course, civil disobedience means nothing if it fails to disrupt, and that's the dilemma of "Ten Visions." Stanley Tigerman, the show's "master planner," provided the ten architects with his own gallery/condo, a 21-foot-square room in which to curate an exhibit. He calls the resulting diversity "a healthy forward movement in which no one style or look dominates." The result is an enormous range of architectural thought, but the question remains: is diversity enough to inspire vision in our increasingly Wal-Mart culture?

Back in 2000, when the it's participants were chosen, the show's proposed title was "Millennium Chicago," but like the park, the opening was delayed until this year. Tigerman's idea was that all the entries would express alternative visions of the "dream" and/or" nightmare" that might be Chicago's

future, separated in each gallery by a diagonal truss.

Ronald Krueck's starkly minimalist The Rectangle: Vision of the Essential is an enigmatic all-white room bisected by a giant white rectangle that hovers over the heads of visitors like a blade, while Eva Maddox's Chicago Public Education: Future Learning Environment seems less a piece about architecture than a meditation on Howard Gardner's concept of seven types of human intelligence. You almost have to decompress from one gallery to the next to keep from rushing through them-most seem too complex to be captured at a glance, and those that don't may seem too simple to merit attention.

The Snare of our Brave, Virtual World

A good place to start may be Valerio's The Enigma of a Room. Physically, this installation consists of 16 brushed-aluminum plates of varying shape and size placed seemingly at random throughout the room. But as displayed on four monitors showing live feeds from pinhole cameras perched overhead, the contents of the room resolve into a set of four perfectly identical boxes of uniform height. You stand in front of a monitor and see yourself enclosed in a box that doesn't exist in reality. It's a sly demonstration of the way representations of architecture - drawings, photographs, and even

today's amazingly detailed computer simulations - can distort and diminish the way we actually experience architecture in the physical world. Valerio obviously intended this as a serious commentary. But on the day I visited the gallery it had been invaded by a band of eight-to-ten year-olds who transformed his cautionary tale into a funhouse, jumping in and out of the virtual boxes and positioning themselves where, on-screen, they could cut off their hands and heads. They got the point right off, and spent the rest of their time enjoying its implications. It reminded me of the giddy "pop" exhibits at the Museum of Science and Industry used to have when I was young, before technological wonder could be found at any Best Buy. Watching those kids make the gallery their own, I suddenly felt freed from the constraints of adulthood, of consuming culture as if it were brussels sprouts. And that's just the right state of mind for taking on "Ten Visions."

MORE IMAGES OF The Enigma of the Room

In UIC professor Xavier Vendrell's installation Reading Between the Streets, the dream and the nightmare are two Chicagos, one a living "city of relationships...of shared cultural and social spaces...opportunities, density, diversity, and plurality," the other a dead anticity, a place "full of nonplaces" where "new elements do not create new relationships or cultures." Think big-box retailers set within massive asphalt parking moats, or burned-out neighborhoods where the vacant lots outnumber the buildings still standing. Vendrell expresses the concept of the two cities through two series of streetscape photographs, both covering the walls and printed on a series of tall glass panels. But I have to confess that I strained to find the contrast-to me all the depictions felt equally unsettling and alienating.

The Ballpark as Heaven and Hell

Architect Jeanne Gang's Baseball in the City: Change and Density does a better job of embodying the contrast. "Wrigley is more like the dream," she says, "and U.S. Cellular is more like the nightmare." Wrigley Field meets Vendrell's criteria for the city of relationships: the surrounding neighborhood  buzzes like a beehive whether it's game day or not. The area around U.S. Cellular, on the other hand, becomes an urban necropolis the moment the stadium empties. buzzes like a beehive whether it's game day or not. The area around U.S. Cellular, on the other hand, becomes an urban necropolis the moment the stadium empties.

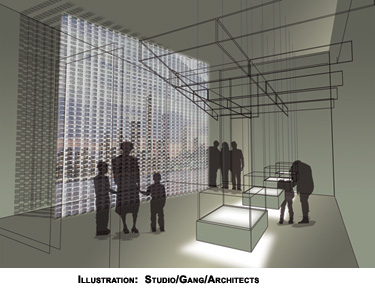

Gang is becoming a master at pushing materials and structure to new heights. Earlier this year she designed a hanging curtain made entirely of marble for an exhibition at D.C.'s National Building Museum.

The centerpiece of her installation here is a 14-foot-high wall of 15,000 baseball cards, bent to provide strength and stiffness, stapled together, then hung in columns joined with fishing wire. One side of the wall consists of actual baseball cards, but the inside facing, which from a distance resolves into a picture of a skyline, includes cards with facts gathered in a collaboration between Gang's firm, Studio Gang, and IIT students to analyze the impact stadiums across the country have on their home cities.

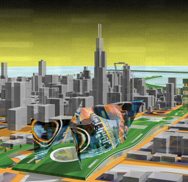

Based on this research, Gang and her students came up with four models illustrating different ideas for reurbanizing Sox Park. One proposal is to encase it in a megastructure that includes parking and big-box retailers. Another is to place it in a "land bridge," a swath of parkland that would

flow under the Green Line and over the Dan Ryan, a barrier that has historically separated white and black Chicago. A third envisions creating a Wrigley-like residential neighborhood all around the Cell; grass interwoven with drive-on pavers would abut the new houses, providing yards that could be rented out as parking, in time-honored Wrigley tradition. The last model starts over completely, placing a new stadium smack in the Loop, built atop a parking garage that's lined with retail along the street sides. For night games, it can also draw on existing parking garages that empty out after 5, and enhance the Loop's emerging status as a 24-hour neighborhood.

MORE IMAGES OF BASEBALL IN THE CITY

Taking Affordable Housing Beyond Subsidies

The optimistic big idea of "Ten Visions" is that good new architecture has the power not only to displace the bad architecture and planning of the past but to address social ills. In Margaret McCurry's To Dream..., which explores affordable housing, one wall is filled with statistics; on another there's a slide show of housing projects next to a smiley-face icon that gets less smiley as the building gets worse. One of McCurry's collaborators, Annex/5 architect Andrew Metter, takes the issue a step further. "There's no such thing as affordable housing," he argues. "It's all subsidized by the government. So the idea was to design a new topology: a house and a job. It's a new building type and mental construct-not just build homes and figure that people will get checks from the government, but build it in conjunction with income-producing opportunities."

Metter also uses "found infrastructure"-train lines and river embankments, pathways that "cut through all kinds of neighborhoods virtually, economically, physically"-for construction that arrests gentrification. Along the el, he says, "the idea was to reclaim the ground for income-producing activities: hothouses, farmers' markets, etc....The other idea is that along the river you establish manufacturing." In Metter's rendering, "the factories are sunken, submerged. The roofs are reestablished as 'ecoparks.' The city's conservation easement is about 50 feet wide, but I expand it to about 150 feet, with the factories underneath and housing for the people working in those factories above."

Can Yesterday's Bad Idea Become Today's Vision?

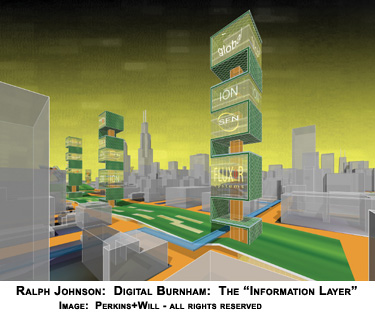

Metter isn't the only "Ten Visions" architect thinking about stitching back together the urban fabric that's been sliced by modern transportation. Last year architect Ralph Johnson of Perkins & Will created a stunning vision for the Chicago Architecture Foundation's "Invisible Cities" exhibit: a

proposal for concealing the toxic gulch of the Kennedy Expressway under a series of land bridges bearing museums, restaurants, shops, and parkland.Digital Burnham: The "Information Layer," his "Ten Visions" entry, fills in and updates Daniel Burnham's 1909 Plan of Chicago by building, at the

Halsted and Congress location where Burnham had envisioned it, a new City Hall set beneath a green roof. It's flanked by a pair of ten-story sculptures that reimagine Richard Serra's Tilted Arc as massive digital billboards. As with the Kennedy in Invisible Cities, in Digital Burnham both the Congress expressway and Congress Street are covered over with a continuous strip of parkland, here topped with widely spaced, technologically innovative office towers, that extends east of Lake Shore Drive as a causeway leading to a new airport in the lake. Halsted and Congress location where Burnham had envisioned it, a new City Hall set beneath a green roof. It's flanked by a pair of ten-story sculptures that reimagine Richard Serra's Tilted Arc as massive digital billboards. As with the Kennedy in Invisible Cities, in Digital Burnham both the Congress expressway and Congress Street are covered over with a continuous strip of parkland, here topped with widely spaced, technologically innovative office towers, that extends east of Lake Shore Drive as a causeway leading to a new airport in the lake.

Johnson appears amiably oblivious to the fact that a lot of people - including, it would appear, Mayor Daley himself - find the idea of an airport in the lake an abomination. “It's more viable now,” Johnson argues. Isn't it a better idea than still more urban sprawl destroying vanishing wetlands or prairies? Green technology mitigates the environmental impact, and all the pollution created and energy spent on those long treks to and from O'Hare are eliminated. Most importantly, in Johnson's view, it's would offer the chance to plug the city directly into globalization's raceway. Instead of a Peotone, tearing up farmland to create new Rosemonts 40 miles south of the city, Johnson's airport plugs directly into existing infrastructure, its extended concourse downtown Chicago itself.

MORE IMAGES OF DIGITAL BURNHAM: The "Information Layer"

Do Architects Have a Place at the Planners' Table?

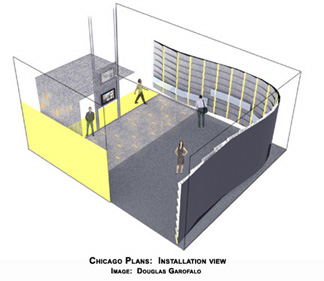

Burnham's plan acknowledged the central importance of architecture to the city by illustrating it with renderings of the stunning neoclassical buildings he envisioned. Nearly a century later, when the Commercial Club of Chicago-the same organization that commissioned Burnham's plan-issued

the new blueprint Chicago Metropolis 2020, the 118-page report was completely devoid of imagery. For Chicago Places, his "Ten Visions" installation, architect Douglas Garofalo enlisted college students from four different local schools to "illuminate" the plan. In one student's project a stretch of highway is woven into a surrounding nature preserve to transform it from a barrier into a permeable greenbelt that "oscillates between city, suburb and nature." In another the Cumberland Rapid Transit Station is wrapped with housing and a green roof to decrease its isolation

from the surrounding neighborhood.

MORE IMAGES OF Chicago Places

We Must 'Disinthrall' Ourselves

Metropolis 2020's often Olympian focus shows a singular lack of curiosity about the human processes that create the conditions it analyzes. Architects, however, work in the street, and their visions are tempered and informed by the highly specific and often painful realities of everyday life-for example, dislocation. In Chicago, City of Arrivals, Katerina Ruedi Ray argues that the future of Chicago belongs to its children and immigrants, two groups immersed in a state of "estrangement" from their new environment that hangs in the balance between enchantment and alienation. One side of Ray's space documents the immigrant's experience of the INS office - the passport photo stores outside, the endless rows of filing cabinets and bare fluorescent bulbs inside. On one wall two small posters reveal the green-card status of Ray and her collaborator, Igor Marjanovic-resident alien and temporary worker, respectively. The midpoint of the installation includes clothes and tools from the construction workers who built it, all of whom signed their names on the bare wood, underscoring says Ray, that “immigrants form a huge part of the construction industry here.”

The enchantment side features shadow boxes by fourth graders at Pilsen Academy, who were asked to imagine the future skyline of Chicago, using only the a content of a bag of materials randomly assembled for each child. A Louis Sullivan sketch forms the background of each box. “It's funny,” says Ray, “because all the boys got these really decorative frames just by accident.” “But,” noted a bystander about an ornate frame in one box, “there's an alien monster inside.” A copy of a Louis Sullivan drawing forms the background of each box.

In a thin strip that stretches across the walls is text from a Walter Benjamin meditation on childhood

“He's one of the few people,” says Ray, “who links childhood and urbanism. Each new generation, basically, reinvents the world.”

Benjamin likens childhood to dreaming, to a time in life when the things we encounter have not yet been locked down to the certainty of the familiar but bear the possibility, in terror or delight, of the imagined becoming real. He sees creativity as the ability to rescue childhood visions "out of the dangerous magic realm of mere fantasy and to bring them to bear on material stuff."

Do You Really Want to Know How the Sausage is Made?

That same creative process - in the specific guise of how architecture actually gets built - is the subject of Elva Rubio's Views. "We chose humor, first of all, and storytelling about how the city

is made, how decisions are made," she says. There are Dada-esque faux newsreels on the creation of the renovated Soldier Field, Millennium Park, and the new Maxwell Street. And there's a series of  colorful viewing boxes spinning a tale about the Miro sculpture (rechristened as the "Goddess of Love and Beauty") escaping its spot on the plaza across from the Daley Center to wander through the city, cleaning the river, growing food in planters, and spreading grace. colorful viewing boxes spinning a tale about the Miro sculpture (rechristened as the "Goddess of Love and Beauty") escaping its spot on the plaza across from the Daley Center to wander through the city, cleaning the river, growing food in planters, and spreading grace.

The goddess is even pictured as an adviser to Mayor Daley, in a video that imagines the transformation of the Lake Calumet area from polluted cesspool to pastoral paradise. The video, says Rubio, "focuses on the year 2150, which is seven generations from now, which is a way American Indians used to build. Whenever they touched the land, they always considered seven

generations." In 2150, Rubio says, "the Daleys are still in power-but the mayor's name is Ricardo Raoul Daley."

MORE IMAGES of VIEWS

Rubio's team is really the only one to address the process of architecture, and that highlights what is perhaps the greatest shortcoming of "Ten Visions." Tigerman lauds his participants for their bravery in not using the show to display their firms' current work, but the troubling flip side is that none of the projects envisioned in the show are on any kind of track toward being built. "We live in extremely conservative times," Garofalo laments. "The act of getting a progressive, contemporary project built is a rarity."

Architectural Vision: As Trapped as the Miro Sculpture?

"Ten Visions" buys into the mythology that diversity will set you free, but if you're contemplating the redemptive power of diversity to force positive change, consider: for salty snacks, we're given hundreds of varieties to choose from; for political parties, only two (in Chicago, arguably only one.)

"Ten Visions" has a fatal lack of curiosity about how, in the market economy, power continues to consolidate into the hands of an ever smaller number of corporations and developers whose single-minded pursuit of efficiency and standardization is uncompromised by any tolerance for alternate points of view. For them, original architecture is an unnecessary expense; the warehouse store, strip mall, concrete condo tower, and lot-busting town house represent the greatest economic good. These "nonplaces" fuel and expand Vendrell's nightmare city, marginalizing the dream city and shoving progressive architecture to the periphery as a boutique endeavor.

The process of creating "Ten Visions" reflects this marginalization. It took more than four years to bring the show into being-longer, cracks Joe Valerio, than it took us to wage World War II. Such a gestation period may be OK for long-dead painters or architectural retrospectives, but for current-day architecture it's an eon. You can walk all the way through the exhibit without confronting the bollards and bunkers that are icons of the architecture of fear created in the wake of 9/11. More disturbing, while catalogs for "Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand," the Art Institute's current show of ancient American Indian art, are for sale in the gift shop, with copies set out for public perusal, a notice says that for "Ten Visions" a "limited-edition catalog of the exhibition will be made available by request only." Is Chicago architecture a public concern or a secret society?

Although the Art Institute has created a web preview of the show that includes a bio of each architect and brief descriptions of the installations, the only illustrations are basic concept renderings. The actual content of the individual exhibits remains almost completely undocumented. This means "Ten Visions" will repeat the fate of many recent and important shows on Chicago architecture that never achieved a presence on the Internet, today's most critical tool for keeping information available to the widest range of people. (The Chicago Architecture Foundation's Web archive of its recent "Chicago Green" exhibit and current Bridging the Drive are welcome exceptions) Unlike a traveling blockbuster, where at the end the paintings or sculptures return to their home museums, shows like "Ten Visions" simply disappear into thin air. How do you build an ongoing public dialogue on that?

lynnbecker@lynnbecker.com

© Copyright

2004 Lynn Becker All rights

reserved.

|