|

|

This new movement would continue to percolate largely under the radar until the economic boom of 1990s, when it would roar into the foreground with an explosion of construction. 32,000 housing units were added downtown from 1980 to 2001-more than in any other city, with still another 15,000 created between 2000 and 2002. Huge developments like Central Station were created on former rail yards. Residential conversions of historic industrial lofts, coupled with new residential towers, have transformed the long derelict districts on the Loop's periphery into thriving communities. In outlying neighborhoods, old courtyard buildings have been upgraded and converted into condominiums, while new townhouse developments have sprouted like mushrooms, often in the form of teardowns of the historic homes and cottages that gave the neighborhoods their character.

Other than a “reform” plan for public housing, in which fifty-three “gallery style,” often crime infested public housing high rises are being systematically demolished to be replaced by low rise, mixed income communities, the bulk of this development has taken place outside any planning process remotely like Burnham's 1909 blueprint.

This is also arguably the first building boom in memory fueled, not by prestige office towers designed by internationally regarded architects, but by increasingly generic condo towers, the residential equivalent of the warehouse store. The goodies inside - in this case the floor plans, the appliances, the views - are what's important. Spending money on the wrapper is not.

In the revised Chicago skyline, the isolated examples of great Chicago design - Lucien LaGrange's spiky, glass walled Erie on the Park, Ralph Johnson's airy split towered Skybridge, and Jean-Paul Viguier's Sofitel Water Tower hotel, which reinvents the Chicago skyscraper with French elegance, Corbusian geometry, and a bit of Morris Lapidus - struggle not to be overwhelmed by the tidal wave of forty, fifty, and even sixty story mediocrities. Constructed of poured concrete, they offer a perfunctory sense of massing, and ugly above grade garages that cling to the lot line and turn surrounding streets into dead canyons.

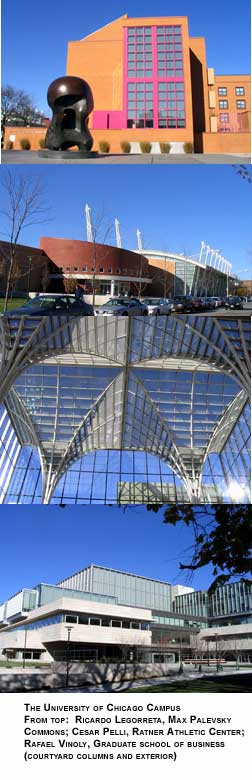

Like learning in the Dark Ages, architecture of the type that won Chicago world renown has largely withdrawn into the cloisters of academia. Just last year, striking new buildings by Rem Koolhaas and Helmut Jahn opened on the IIT campus. At the University of Chicago are Cesar Pelli's brawny Ratner Athletic Center and new dorms by Ricardo Legorreta. Last fall, Rafael Viñoly's University of Chicago Graduate of School of Business opened just across the street from Frank Lloyd Wright's Robie House, which is reflected in the boxed massing of its new, far larger neighbor, just as the flaring cylindrical columns of Viñoly's winter garden evokes both the dominant Gothic traditions of the campus's architecture and Wright's own flaring lily pad columns in the Johnson Wax Building.

You won't find the names of any of these architects on any of the residential towers in downtown Chicago. The same free market economics that fueled the city's turn of the-21st-century boom has proved that you can sell a lot of condos without caring much about architectural quality.

The city of Chicago's priority in all this seems to have mostly been about getting every last drop of development on the tax roles and dealing with the consequences only after they became fact. It was not until this past year, after most of the building and most of the damage had been done, that the city got around to finalizing a new Central Area Plan, which codifies the already operational concept of moving new office development to a location away from the Loop, west of the Chicago River.

Next: Making the Sausage - A boom and its architecture

Next: Making the Sausage - A boom and its architecture

Introduction - Not Entirely What Burnham Had in Mind - Chicago's Future

lynnbecker@lynnbecker.com

© Copyright

2005 - Photos and text by Lynn Becker All rights

reserved.

|